The anatomy of hedge fund liquidations and key screening factors for investors

By Daniel Huss; Stephan Paul, Prime Capital AG

Published: 18 November 2024

Executive summary

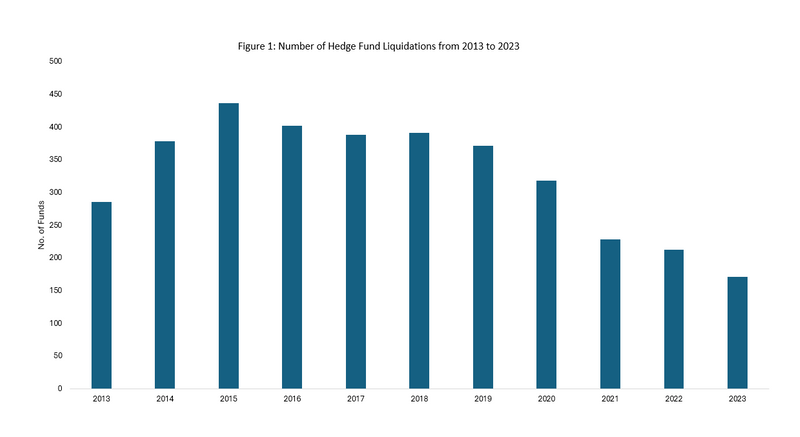

Hedge funds attract investors with the prospect of higher liquidity, uncorrelated returns, low volatility or a combination of these in comparison to other alternative investments. However, this frequently involves the use of complex financial instruments, leverage and trading strategies associated with significant risks which, due to the secretive nature of hedge funds for protecting their competitive advantage, can be difficult for investors to gauge. Based on a dataset from Preqin Pro of self-reported performance data just over 3,500 hedge funds were liquidated between 2013 and 2023. Such liquidations may be involuntary or voluntary at the initiative of the manager and the impact on investors can vary widely depending on the cause and type of investment strategy. In the following we elaborate on causes of failure, differentiating between performance and operational issues to show ho each scenario can impact investors through opportunity cost or losses and last what measures investors can take to avoid such cases.

Opportunity cost

When managers underperform against benchmarks or expected risk-adjusted returns, investor confidence erodes and key talent may depart, leading to redemptions and potentially forcing the manager to liquidate the fund. Continuous underperformance ultimately results in opportunity costs for investors, which is further exacerbated over time and directly impacted by the redemption terms and asset liquidity.

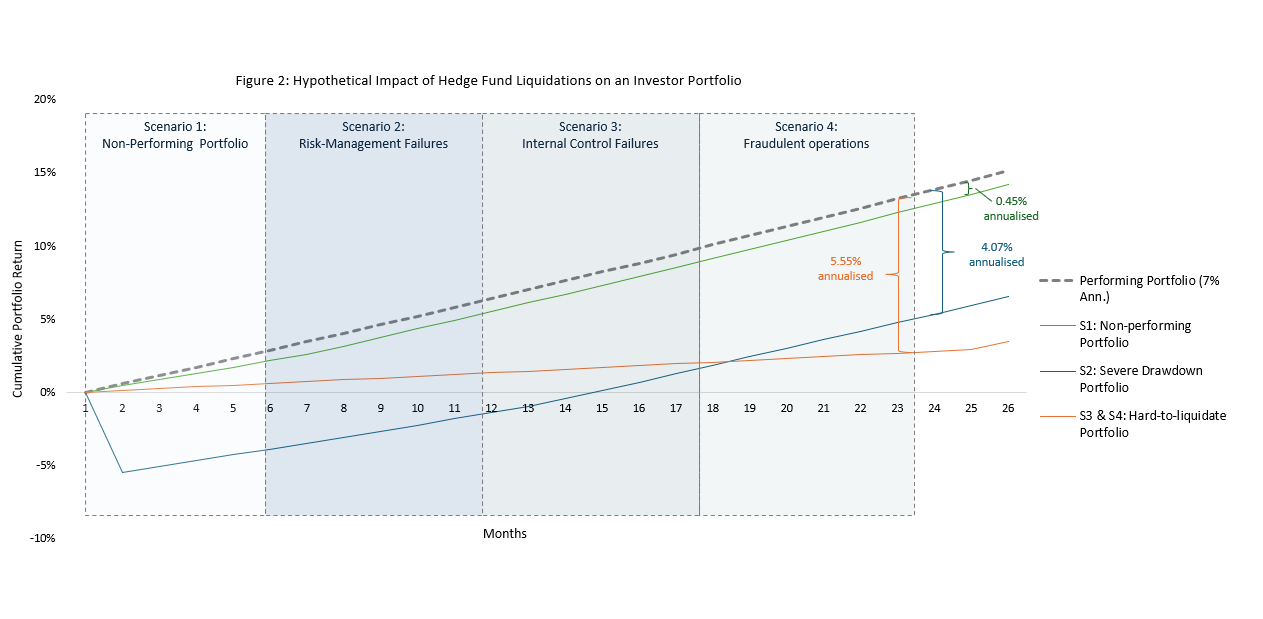

Whilst performance-related issues play a significant role, with 86% of liquidated funds in the available data that reported target returns having underperformed prior to liquidation, operational factors also come into play. High prospective management and performance fees have historically driven individual managers to override risk-management or internal controls, pursue strategies at odds with laws and regulations or conduct outright fraud to the detriment of investors. As illustrated through different hypothetical scenarios in Figure 2, these operational failures can have a significantly larger financial impact on investors.

Scenario 1 (S1) assumes a non-performing portfolio with 0% rate of return on the affected portion and a 6-month liquidation period with no cost to liquidate. Scenario 2 (S2) assumes a risk-management failure leading to a 25% drawdown on the affected portion followed by a 6 to 12-month liquidation period assuming a 5% cost to liquidate. Scenario 3 (S3) assumes an internal control failure leading to a 0% rate of return on the affected portion of the portfolio with an 18-month liquidation period and 10% cost to liquidate. Scenario 4 (S4) assumes fraudulent operations leading to a 0% return for the affected portion of the portfolio with a 24-month liquidation period and a 10% cost to liquidate. The affected portion of the portfolio is 25% in each case with the benchmark portfolio earning a 7% annualised return.

Scenario 1: Non-performing portfolio

Liquidation involves selling the portfolio to pay investors, with timelines varying by asset liquidity. Liquid assets such as listed equities can be sold in minutes or days, while illiquid assets like private securities may take weeks to months. In rare cases such as a severe liquidity mismatch, liquidation can exceed 1-2 years. In a normal winddown the manager can exercise control over the timing of portfolio liquidation to ensure minimal cost, and the best outcome for investors. A fire sale can disrupt markets, hence from an investors’ standpoint an extended sell-off period can be preferable to protect the value of the portfolio, especially for illiquid assets and low-volume markets.

Scenario 2: Risk-management failures

Failure to capture complex instruments within the risk-management systems or to establish an effective risk control framework can result in drawdowns. These can be significant and unexpected, leading to the fund being so far below its high-water mark that earning performance fees in the foreseeable future becomes unlikely. This often causes investors to rush for the exit, requiring managers to liquidate and potentially discontinue operations. Investors should reasonably assume a 6 to 12-month liquidation period, as the outsized drawdown and redemptions may trigger gating provisions or extended sell-down periods to ensure adequate pricing. While an effective risk-management system capable of measuring and aggregating all risk exposures over the portfolio as well as subjecting these to historical and scenario-based analysis is intended to prevent such drawdowns, black swan events do occur, and some managers may override risk-management warnings and underrate the probability or impact of adverse outcomes. Frequently, the risk-management team cannot directly intervene to reduce risk, which is where clear escalation lines and communication channels to senior management and the board of directors are required.

Scenario 3: Internal control failures

Investment activities using material non-public information, market manipulation, front running or sanctions circumvention have been used to try and gain an edge. Once authorities become aware, assets may be frozen and investors must await the results of legal proceedings which, in severe cases, become liquidation proceedings in which investor gains may be clawed back be clawed back by liquidators as ill-gotten. The length of the legal proceedings will depend on the capacity and efficiency of the courts as well as the complexity of the case. Prosecution may be prolonged due to the need for evidence of collusion, proof of the use of material non-public information or dependence on collaboration with foreign authorities when identifying alleged sanctions circumvention. These generally are shorter than in the case of fraudulent activities as funds have not been embezzled.

Scenario 4: Fraudulent operations

Fraudulent operations are those wherein investors are deceived about the nature of the business and range from the use of misleading marketing materials to cases where no actual investments were made, and capital was raised solely with the intent of misappropriation. While easier to prosecute than internal control failures, since existence and performance of assets can be quickly confirmed by the fund brokers and custodians, the potential losses investors face may be significantly higher as spent embezzled funds can be difficult to recover.

Mitigating measures for investors

To avoid lengthy capital lockups from liquidating funds or becoming the victim of fraudulent investment schemes investors should evaluate the following aspects of the business in conducting their due diligence.

1. Strategy evaluation

The strategy and financial instruments used should be examined to avoid having capital locked up for extended periods in winddown proceedings. A liquidity mismatch between traded instruments and offered redemptions can be the first warning sign. Furthermore, investors should monitor whether and to what extent illiquid level 3 instruments are held. These might come with stale prices and lack of an active market meaning a bilateral buyer must be found. Lastly, investors should review the managers’ track record, whether at a previous firm or their current one, to determine whether they have successfully implemented this strategy in the past.

2. Third-party verification and oversight

Under best practices fund administrators confirm 100% of the existence and value of the entire portfolio independently and maintain the official set of books and records to prepare the funds financial statements. The fund administrator should have direct lines of contact with the fund’s counterparties and oversee all transfers of cash and assets. In some instances, the fund manager may need an independent valuation agent to price complex instruments and investors should understand the parameters and assumptions used in models as well as the process for valuation overrides. Measures such as independently confirming managers’ relationships with counterparties and service providers are simple and effective, but still not done by every investor. Auditors serve as the 4th line of defense, nevertheless investors should enquire whether these have adequate resources such as valuation specialists.

3. Risk, legal and compliance framework

An experienced and sufficiently staffed risk, legal and compliance department with established processes is essential to prevent misconduct. Archiving of trading communications, monitoring of personal account dealing, and market abuse surveillance systems make up the baseline repertoire of detective controls used by compliance managers to identify suspicious activity. Effective internal controls when processing financial positions and onboarding new products should ensure that positions are captured in a timely manner and risk-management systems cannot be overridden. Some strategies carry higher inherent risk of manipulation such as those involving infrequently traded or hard to price securities, whereas strategies surrounding highly liquid and regulated products like listed index futures are less at risk, therefore the control framework should be tailored to the inherent risk.

Conclusion

While hedge fund investments offer attractive returns and liquidity, they require a tailored due diligence approach to mitigate the risk from drawdowns or liquidations. Hedge fund failures related to operational factors can lead to more complex liquidation proceedings and higher opportunity costs for investors. Evaluating factors such as the service providers, risk-management and compliance function as well as a thorough evaluation of the strategy are therefore crucial.